- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Featured Post

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Rick Joy Nomad House by Rick Joy Architect

Modern and Contemporary

Architecture and Landscape

in Arizona's High Sonoran Desert

Thursday April 7th, 2006

Rick Joy will lead a tour of his Desert Nomad House (formerly Casa Jax) and the experimental Tucson Mountain House. These two homes are on either side of a small hill, nestled in the mountains. We’ll start at the Nomad House, walk through the desert and over the hill to the Tucson Mountain House (and pottery studio), and then walk back to relax and have a drink and watch the sunset around the fire pit at the Nomad House.

Based in Tucson, Arizona, Rick Joy not only responds to the desert landscape, but sensitively and carefully situates his buildings in their surroundings. Believing in formal simplicity and technical sophistication, Joy’s work reflects his early training as a finish carpenter. His work includes the Desert Nomad House and the Tubac House, recognized by Architectural Record (April 2005) as Record Houses of 2005.

REGISTRATION (PDF- print and return)

This tour is limited to 40 participants.

For more information contact:

Laura Allebach Nichols

Events and Stewardship Coordinator

Development & Alumni/ae Relations

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

617.496.1222

Fax: 617.495.5967

Link of Interest and Sources:

http://www.rickjoy.com/

http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/

http://archrecord.construction.com

Rick Joy:

Architect Rick Joy, originally from Maine, has lived and worked in the desert landscape of Arizona for over a decade. Guided by an abiding fascination with the desert’s capacity for sensory stimulation, and a commitment to functionality and craft that survives from his training and work as a contractor, Joy has developed a modern architecture that cultivates sensory experience, harmonizes with the landscape, and eschews formal pretense. On April 24, The Architectural League and the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum welcomed Joy to discuss his ideas, his work, and the desert which has nurtured both.

“The desert,” said Joy showing slides of the richly colored Sonoran desert, “is a fantastic place in the most correct meaning of the word; it is at times a dreamlike fantasy of a landscape. . . . the desert’s beauty extends beyond objects and things to an atmosphere of place that is defined by quality of light and other sensory kinds of input.”

After graduating from architecture school at the University of Arizona and working several years for Will Bruder, Joy founded his own practice in Tuscon in 1993. His first significant project, for a Canadian developer, was the design of three houses on an abandoned lot in Tuscon’s Barrio Historico. Joy resisted calls to construct “false relics” on the site, instead developing simple modernist rammed-earth one-bedroom loft dwellings that reflect the aesthetic heritage of the site without directly copying it. In the areas around the buildings Joy included features—gravel courtyards, fragrant trees, a fountain sculpture—that stimulate the various senses.

Attention to sensory stimulation, what Joy calls “ethereal, visceral experiences,” guides his design work to such an extent that it often “preempts consideration of the formal aspects of a project. Sounds, smells and tactile qualities are often more important than the shape of the object itself.” Owing to this focus on sensory experience Joy’s architecture, while undeniably rooted in Modernism, avoids the coldness sometimes associated with the style. “To this day,” Joy said proudly, “several of my clients don’t believe they have modern architecture projects.”

Joy’s 1998 Palmer House (featured in the League’s Ten Shades of Green exhibition) is a 2,500 square foot one-bedroom dwelling just north of Tucson that is oriented to provide breathtaking views of the surrounding Catalina Mountains. The rectangular living room wing, an open and airy pavilion-like space, faces the mountains with a broad, full height glass wall. The bedroom wing, also a rectangle, is offset slightly from the living room to allow morning sunlight to enter. The whole project is characterized by attention to environmental detail. A butterfly roof was used to minimize erosion caused by run-off, and the home, set 25 feet below the level of the access road, is almost entirely concealed from view.

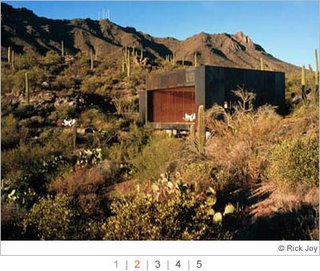

It is crucially important to Joy that his projects rest lightly upon, or within, the landscape. The plan of his 2000 Tubac House in Tubac, Arizona, for example, is defined by two U-shaped retaining walls set into a hillside that gently slopes away from the approach road. Seen from the road, the house’s presence is indicated only by the few portions of the roof that angle up above grade. The entry sequence is carefully choreographed so that the frank rust-colored volumes of the home unfold gradually. One crunches through the gravel driveway above the house, passes through an “army” of barrel cactus, and descends into a courtyard that separates the two main volumes of the house. How the landscape looks from within the house is as important as how the house looks from without. Windows puncture, and in places protrude from, the weathered steel and wooden volumes to capture and frame the surrounding views. “It’s really about taking these enormous panorama views and kind of reframing them and revealing them slowly for different parts of the experience,” Joy explained.

Joy designed his own studio on land left over from the Barrio Historico project. The structure, as he describes it, is “one big monolithic block, a building primarily of walls.” The interior is simple--one large space, divided from an outdoor courtyard by a glass wall, features a drafting area and a conference area. A bathroom is tucked into the thickness of the wall. The ceiling is of galvanized metal with slots for HVAC and sound equipment, and it “floats between the walls like the blue sky does outside.”

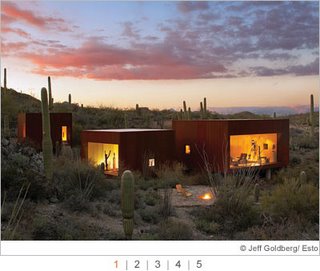

Construction is currently nearly complete on Casa Jax, a set of three rusted steel cubes nestled “like hunter’s blinds” in the brush of the Sonoran desert. The domestic program is divided among the three cubes—one contains living, dining, and kitchen space, another the master bedroom, and the third den/guest quarters. Each is positioned to afford the best views and lighting for its program. The bedroom cube faces west towards a mountain that glows bright orange as the morning sunlight creeps down its rocky face. The living and dining cube faces southeast to frame a rocky hill that is similarly illuminated by the setting sun. The den’s main window frames a desert “still life”—a rocky outcropping. The boxes are clad in a rusted steel skin that is separated from the insulation layers and structure by a space that allows for natural ventilation by convection. “This project,” Joy recalled, “was about doing the right thing in this fragile landscape. It has the most dense forest of saguaro cactus in the world, so the buildings needed to be soft little objects plopped down.”

Pima Canyon House, also in construction, is set on a one-acre site in a gated desert community. This house, with its high, largely unfenestrated exterior walls, focuses in on itself around a walled interior courtyard that opens to the mountains. One enters the house through a revolving steel gate set into the southeast corner of the building, passes through a dark chamber with a small skylight and dripping water --what Joy called a “sensory decompression chamber”— and then ascends a terraced hall to a formal entrance of sandblasted glass.

Currently Joy is collaborating with architects Marwan al-Sayed and Wendell Burnett, to design a 36-room luxury resort hotel in southern Utah. Though planning is in early stages still, Joy envisions a V-shaped plan embracing a wide, craggy, desert “piazza.” Joy is also working on houses for a prominent film director and his daughter in Napa, California.

“I think I can read a place pretty well, because of my experience in the desert,” said Joy who suggested that he may some day return to his native Maine. “For now I promise to keep it up and to really make this work worth it and to do great projects in the future. It’s really just about loving life.”

Source: http://www.archleague.org

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments