- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Featured Post

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

By Clifford A. Pearson

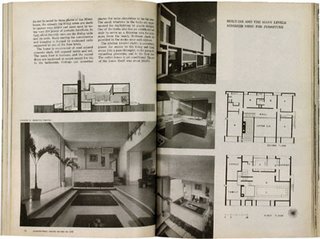

The last of Paul Rudolph’s Florida houses, the Milam House in Ponte Vedra Beach, proved to be a pivotal work in the architect’s illustrious career. Designed after he had ended his partnership in Sarasota with Ralph Twitchell in 1957, it points more to Rudolph’s future than his past, explains Christopher Domin, the coauthor of Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses (Princeton Architectural Press, 2002). While the earlier houses featured lightweight construction, modular organization, and interior spaces opening directly to the subtropical landscape, the Milam House, completed in 1962, takes a more muscular approach to design—using more concrete block and less steel or wood framing, and incorporating large, fixed panes of glass (and air-conditioning) instead of operable windows.

“Sculptural form making was always a part of Rudolph’s work, but he pumped it up a notch in the Milam House,” says Joseph King, the book’s other author. Look at this house and you can clearly see the family resemblance to the much bigger and more controversial Art and Architecture Building at Yale, which opened just one year later. Walk inside and you’ll find the multiple floor levels (seven here) that so captivated (or infuriated) users of Rudolph’s later buildings. “It was a transition for Rudolph, but also for architecture as a whole,” adds King.

It certainly hooked the editors of Architectural Record, who published it no fewer than four times in the 1960s: once as a project, once as part of an article on six houses by Rudolph, then in Record Houses, and finally in a retrospective look at the first decade of that annual issue. Cartoonist Alan Dunn also found the house irresistible, poking fun at it twice in the pages of record. One of his cartoons shows a couple standing in front of the house’s iconic beach facade as a man (the architect? the realtor who just sold it?) drives away and says, “One thing more—it still takes a heap o’ livin’, you know.” The second cartoon shows a party in the house’s famous sunken living room/conversation pit, but adds a second, smaller pit and a host explaining, “That one is for small talk.”

Arthur Milam, the young lawyer who went to his college reunion at Yale in 1960 in large part to commission Rudolph to design him a house, has retired from the bar but still lives in the house. “It’s a great house to live in,” says Milam. “Each room has a different mood, and you get fantastic views of the water.” In the early 1970s, Milam had Rudolph add two ancillary structures on either side of the main house—one for a three-car garage and one for a guest house/studio. Rudolph used the same materials and design vocabulary for the new wings.

Although corrosion from the salt air has required Milam to repair the concrete a couple of times, it’s clear from him that the house still takes a heap o’ livin’.

By Clifford A. Pearson

Reference:

Architectural Record, mid-May, 1963

Source:

Architectural Record

architecture

architecture by paul rudolph

architecture in florida

architecture in sarasota

florida

florida architect

florida architecture

house

houses

minimal architecture

paul rudolph

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments